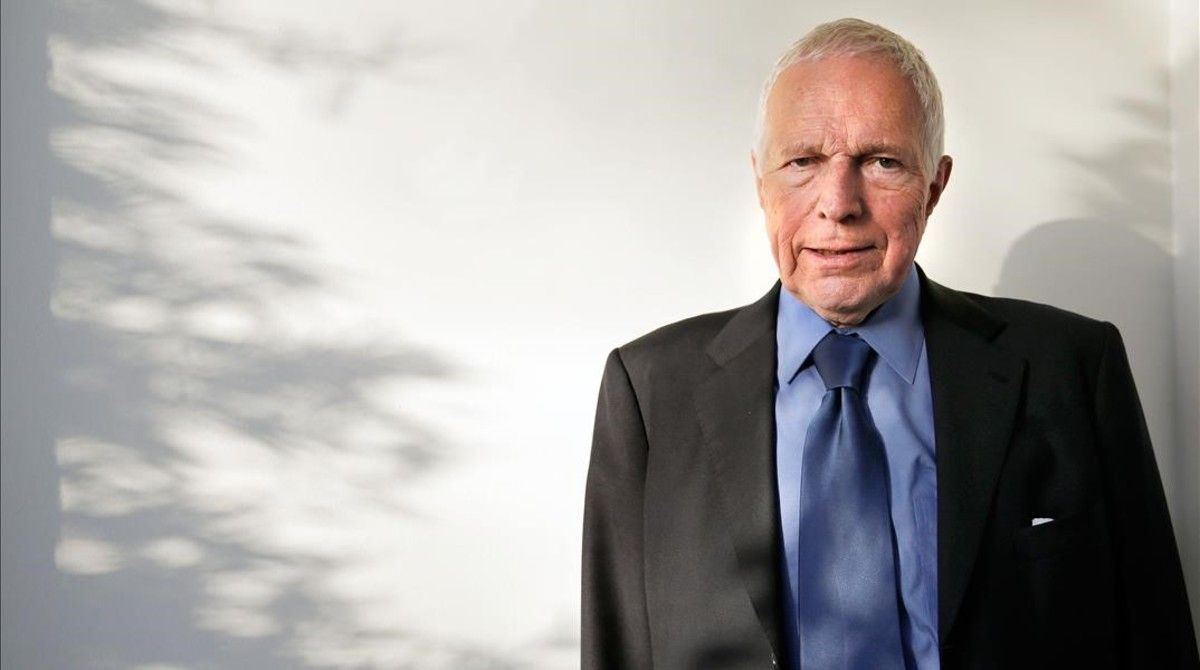

Few Nobel Laureates have spent the amount of time and dug through so much research in the subject of innovation and dynamism as Edmund Phelps, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2006. His current work focuses on the benefits of structural dynamism, creativity, entrepreneurship and the funding of these initiatives. So we talked to him to hear his thoughts on Pittsburgh’s innovative tech scene.

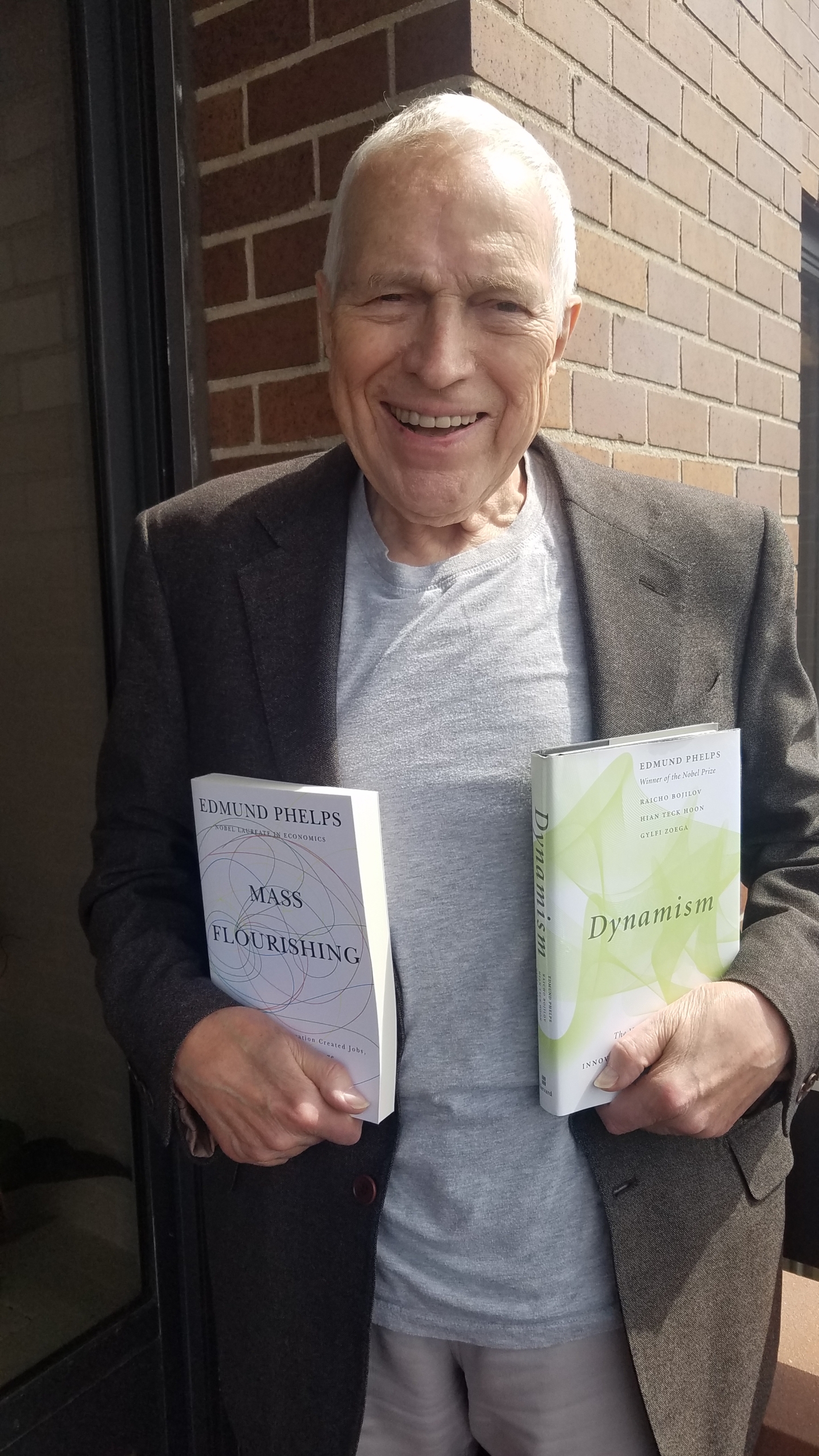

Phelps’ latest book, Dynamism, published in 2020, is loaded with research showing strong correlations between modern values and innovation, with benefits that permeate throughout the entire economy. So what are these values and how does Pittsburgh stack up to them? Phelps’ research uncovers three key modern values that promote dynamism: individualism, vitalism and self-expression. That is what he likes to call “the right stuff.” Let us elaborate a bit… Individualism focuses on the inherently individualistic satisfactions of achieving, succeeding, flourishing and making a difference. Vitalism refers to people looking to challenge the status quo and looking for opportunities that make them feel alive. And self-expression is about being allowed and inspired to create a new thing in a new way, where a person has license to reveal a part of who he or she is. “One of the exciting things about innovating is the venture into the unknown. That’s so exciting and so much fun. You’re venturing into the unknown in the process of trying to create things,” Phelps comments enthusiastically.

One can easily argue that Pittsburgh checks all three boxes in both its innovative heritage and its current thriving tech scene. However, if we dig a bit into the fine print, individualism in Pittsburgh could be interpreted to be on the fence. Phelps contrasts values of community solidarity and staying in a circle of friends as traditional, anti-modern values that do not necessarily promote dynamism. So we asked him, in a highly collaborative culture like Pittsburgh’s, with a tight tech ecosystem, could this cultural trait hinder the city’s innovative spirit? “I’m glad you raise that question, but what I would say is that if Pittsburgh is doing well, and I see that it is, that is not evidence that every attribute of the people in the city is in the service of dynamism. There could be some attributes out there that are working in another direction. It could be that Pittsburgh could do yet a lot better if it had more individualism. But you haven’t killed individualism just by observing one causal influence when there are three or more causal influences at work.”

Let us suppose Pittsburgh could do better, injecting more individualism into its culture – easier said than done in any culture – how do you breed the right stuff into a community? “To the extent that you could have more of it, the cultivation of the right stuff begins in school. School is a place where kids can be introduced to all sorts of aspects of life that they didn’t know existed. And also parents chatting with the children at the dinner table, the kids get to learn a little bit about what goes on in the business world and how parents get satisfaction from their work. And if you don’t have these things, it’s kind of tough. It’s one of the disadvantages that the disadvantaged have to bear, that they have been so cut off from what other kids have grown up with.”

We’re all too familiar with issues of inequity and lack of diversity, a top-of-mind item in the local tech community’s agenda. If the disadvantaged are not finding sufficient help in school or at home, how can the community rise to the occasion and embrace them? “I think that companies must make it a policy to give opportunities to the disadvantaged. Sure, a firm is not going to love everybody that comes through the door, but when it looks like there are grounds for hope, something about a kid that inspires confidence, then it’s important to give him or her the opportunity.”

Phelps puts a lot of weight into a culture of creativity and approaching work not as a chore but as a vehicle to release one’s creativity, which he sustains has lost steam in America’s post-innovative boom. “All the instruments of society could be enlisted to teach people the importance of work. Work is its own reward and it gives people a chance to exercise their creativity; we all have it, you know? And to build up self esteem. And you can’t just let the schools handle it. It’s also the job of the government and quasi-public entities. But there’s so much talk these days about dynamism as if it was residing in some institutions or economic policies or in science. There’s not enough recognition that dynamism comes from the people. The reason why America was so prosperous for so many years, more than a hundred years I would say, is because people possessed a lot of dynamism. They acquired that dynamism by having the right values. Dynamism is essential, there’s no substitute for it. Without the dynamism, forget about it.”

But dynamism also needs funding and we’ve heard many Pittsburgh entrepreneurs call out the shortage of venture capital making its way into local startups. “It is important to set up institutions and hubs where companies can feed into and share information to finance startups, and I think it’s one way in which access to capital can be improved. The main effort ought to be to fuel the innovation that will bring increased incomes to the communities. These hubs are very important.”

Assuming the right values and the right funding, say all the right stuff, dynamism is perceived by many as a threat. Advancements in robotics and AI are paving an accelerated path to automation, threatening wages and jobs. Phelps’ book recognizes two types of robotics – additive and multiplicative. Additive robots can perform the same tasks as a human and therefore act as a substitute for a human worker. But advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning have given way to multiplicative robots, which augment the power of labor. When multiplicative robots are introduced they have a negative impact on wages in the short term, but in the long term they make each worker’s productivity higher, thus increasing wages.

“Robotics will at first displace labor, but in the long run it increases the productivity of labor so to some extent that may also be true of new kinds of robotic technology coming out. It will be two-sided, it will have some benefits as well as short term harm, but we’re a long way away from understanding where the long term effect of robotics will be.”

In a previous interview, Phelps claimed that “the machines can’t produce the new ideas that Hayek and Keynes and Samuelson had” in economics. With developments in AI, vertiginous processing speed and access to monstrous amounts of data, robots are learning to perform highly creative and intellectual tasks like writing a piece for chamber music or performing surgery. Can robots develop economic solutions as well or better than human economists? Phelps’ view is not dismissive, but hesitant. “I can see that some robots may prove to be successful at creating. I know it’s a kind of a hard notion to get over, but it’s hard for me to think that a robot is born with creativity. Robots may be designed in such a way that if they are confronted with a new environment, they will react in new and unexpected ways and it may look like creativity.”

And when robots or AI get creative, who makes the call about the ethical decisions of their creative solutions? “Industry has to some extent already established panels to set up standards and provide advice to users and developers. We need to acknowledge that the indiscriminate use of robots could be dangerous to some subset of people. But throughout history new things have sometimes been dangerous, and society got on top of it and took steps to protect people from some of the harms of some new methods of production. We’re already seeing the emergence of bodies looking into the ethics of robots. I would start at the industry level and see whether they can set up their own bodies to protect people. They can see that it is in their best self interest to do that.”

We asked Professor Phelps to share a fun Pittsburgh anecdote with us. While he came many years ago to deliver a speech at Carnegie Mellon University, he recalls a more random and accidental experience. “Once I was on a plane from Los Angeles to New York and we had dark winds, snow and everything and it had to land in Pittsburgh. So there was a planeload of people on this bitterly cold, damp night, all standing there in a corridor, nobody talking to anybody. And I looked across and there was Marlene Dietrich. So there’s a Pittsburgh story for you.”

A devoted classical music aficionado, Phelps played trumpet in his high school band’s brass section. So we had to ask him if he’d ever seen the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in concert. “I missed it! Many years ago I just left London and they played at the Royal Albert Hall and everybody wanted tickets to that, and there it was, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Did I see it? No, I was on my way back home. But I did read the reviews and I was so envious because the reviews said how fantastic the brass section was. So I hope you can bring it back so I can see the brass section. Send them my way please.”

We’ll try to convince Mr. Manfred Honeck to pay a visit to Carnegie Hall for Phelps to see Pittsburgh’s awesome brass section. In the meantime, better yet, we extended an invitation to Phelps to see it at “home,” and by the way see first hand all the cool innovation and dynamism coming out of here.